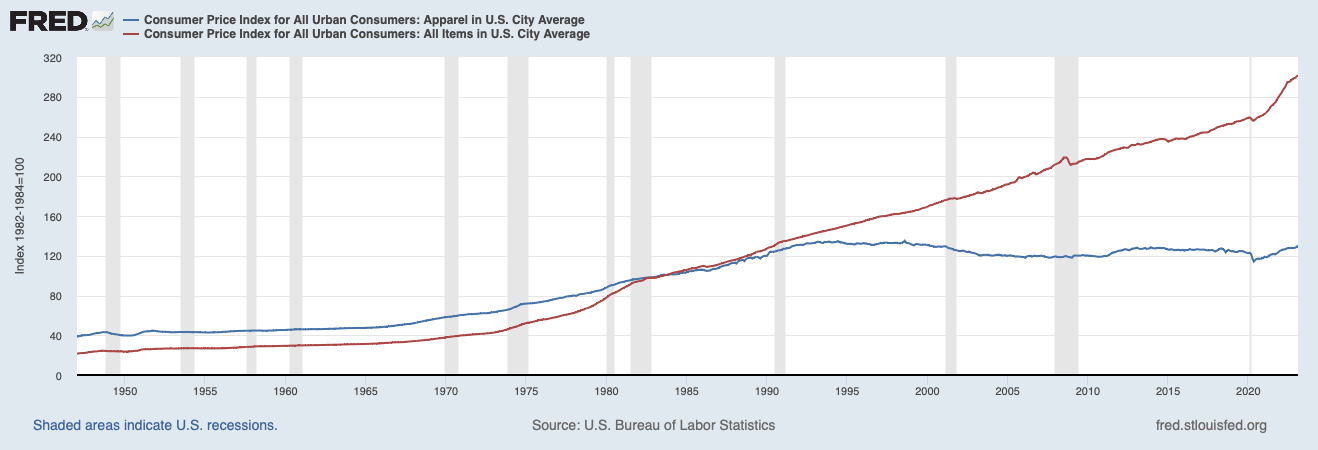

The "logo" for this column isn't a logo but represents the graph that compares U.S. apparel prices to overall inflation. Why did I choose this for a logo other than that it was easy to create? To me, this graph summarizes everything wrong in fashion. Apparel prices aren't cheap because of technological advances, but exploitation across the value chain. Cheap apparel prices help fuel overconsumption and fashion's outsized environmental impact.

Before the 1990s, apparel prices largely tracked overall inflation in the U.S. as they better reflected the true cost of production since most of our clothing was produced domestically. (Please note: this column is written from a U.S. perspective, but the lessons apply globally.)

Source: https://www.stlouisfed.org

The proportion of domestically produced clothing started declining in the 1980s and never looked back as trade barriers fell with the NAFTA and WTO trade agreements. Companies sent production offshore due to the "comparative advantage" developing countries provide(d).

In economic terms, a comparative advantage exists ceteris paribus — all else equal. In reality, that's not remotely the case. The advantages offshoring provides are:

relatively cheap labor (i.e., people paid less than living wages)

lax labor laws giving companies access to easily exploitable and/or illegal workers and/or child labor

loose environmental regulations so brands can pollute without penalty

and then there's the unaccounted-for increased emissions from shipping raw materials and finished goods back and forth across the globe (a post for another day)

All of the above are well documented issues and simply how fashion does business today. It’s overlooked because shareholders want constant growth, and consumers want endless variety and cheap prices. Relatively cheap apparel prices enable consumers to buy more than ten times what they used to while spending less and less as a percent of their total disposable income.

Neither companies nor consumers pay for the externalities offshoring created.

In high school, in the early 1990s, I had a part-time job at The Gap. A short sleeve white pocket tee was around $19.50, roughly $45.00 in today's dollars. In the 1990s, The Gap was more expensive than Hanes or other mall brands, but it wasn't considered a luxury brand by any stretch of the imagination. Today, most think $45 for a plain white tee is fairly expensive.

While this is an older survey from 2020 and one of UK/European consumer attitudes, not U.S. customers, it illustrates how much or how little consumers are willing to pay for a "sustainably made" tee. The most the average consumer surveyed was willing to pay for a “sustainably made” tee was about €15 (US$17) — less than the 1990s nominal price of a white pocket tee shirt.

Again, apparel prices haven't come down due to technological improvements. Robots don't sew our clothes, people STILL sew our clothes. Companies did not get more efficient at making our clothing, but better at exploitation.

An earnest sustainability plan would be a volume reduction plan aimed at increasing margins.

Margins, along with quality, at most fashion brands have been falling for decades, a trend the 2008 financial crisis accelerated, as fast fashion became the norm. Clothes seem to be getting cheaper and more disposable by the day with the rise of ultra-fast-fashion brands like Shein and the various no-name trendy "brands" available on Amazon or our social media feeds. The waste is obvious, but the breadth and reach of these brands have helped shape and anchor consumer price expectations which are already grossly misguided after three decades of price lags.

A Starbucks latté is more expensive than most of what Shein sells. Think about that: a seven-dollar coffee that takes roughly five minutes to make is the same price as a tee shirt or any number of garments from a variety of retailers. Even the poorest quality tee shirt takes more than five minutes to sew. Yet we value our coffee more than our clothes.

If we ever expect fashion to become more sustainable, we need to do the math when it comes to the price of our clothing and to value our clothing.

Today, a white pocket tee shirt from The Gap is still around $19 and is currently on sale for 50% off.

These days we usually get what we pay for when it comes to quality, and sometimes we overpay for what we get as companies spend more on marketing than quality production.

The Rana Plaza tragedy happened ten years ago this month. Apparel prices remain flat, while revenues and profits have soared across the fashion industry. The S&P’s Apparel Retail Sub Index has more than doubled over the last ten years — and that index wouldn’t include the likes of a Shein and other international fast-fashion juggernauts and others.

Progressive consumers and activists keep calling for greater transparency and accountability in fashion, but is there anything more transparent than the price and all it represents?

Why aren’t they calling for more people to simply do the math?

P.S.

For all the Gen Xers reading this note, here's a trip down memory lane: Remember the 90s Gap commercials? Remember how long the tees, khakis, cords, jeans, or just about anything you bought from The Gap in the 1990s lasted?

Who needs endless volume and variety when you got that kind of value from your clothes? That was sustainable fashion before we ever even knew what that was.